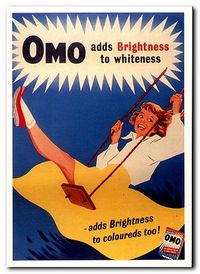

Two novels have recently been published with the aid of 'sponsorship' deals by commercial enterprises. Cathy's Book is about a teen whose boyfriend dumps her. Procter & Gamble came to an arrangement with the authors for them to include mention of products such as 'Shimmering Onyx' eye shadow and 'Metallic Rose' lipstick in exchange for promoting the book on their website. This is what's called 'product placement' which just in case you weren't aware of it occurs (usually in films and TV drama) when commercial products are inserted into the narrative as a form of low level or subliminal advertising. Television now takes quite a robust line against this practice. No well-known breakfast cereals are allowed to be on the kitchen table in your favourite soap.

Two novels have recently been published with the aid of 'sponsorship' deals by commercial enterprises. Cathy's Book is about a teen whose boyfriend dumps her. Procter & Gamble came to an arrangement with the authors for them to include mention of products such as 'Shimmering Onyx' eye shadow and 'Metallic Rose' lipstick in exchange for promoting the book on their website. This is what's called 'product placement' which just in case you weren't aware of it occurs (usually in films and TV drama) when commercial products are inserted into the narrative as a form of low level or subliminal advertising. Television now takes quite a robust line against this practice. No well-known breakfast cereals are allowed to be on the kitchen table in your favourite soap.

In another case, even more incredibly, men are being targetted to buy household applances. Swedish-based appliance maker Electrolux commissioned the improbably titled Men in Aprons. It's the tale of a guy who has to master housekeeping after his girlfriend moves out. The text doesn't mention Electrolux, but the cover does, and the end of each chapter has tips for a tidy home with generic mentions of appliances which Electrolux sells.

In literature there has always been mention of brand names. James Joyce even made a point of qoting an advertising gingle in Ulysses

What is home without Plumtree's Potted Meat?

Incomplete. With it, an abode of bliss.

The sponsors argue that there's nothing new in all this:

all of the major literary prizes are sponsored by corporate money, so they [the writers] don't mind taking the corporate money when it suits.

But this misses an important point. There's a big difference between accepting prize money after a book has been written and published, and taking money up front with a brief to write to order.

Literature has never shied away from mentioning the products of the real world. But there's something a bit odd about producing a work of fiction which has as a given that it must mention the sponsor's widget.

We'll read and be waiting for this moment. And when it arrives we'll think 'Ah - there it is.' And then we will pass on, safe that the aesthetic raison d'etre of the piece is over.

I might be wrong, and I have nothing against writers getting paid in any way possible (speaking as a writer) - but somehow, this stinks.

more Modern Fiction here

1 comment:

Roy

I agree but similar splenetic reactions were made by our parents' generation when ads first appeared on independent television and, arguably, we've got used to that by now; so maybe the same thing will happen with this corporate intrusion into creativity. I hope not.

Post a Comment